April 25, 2002 — Twice during the period encompassing the 2002 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, University of Utah physician Per Gesteland received an automatic alarm signal through his pager. He rushed to his home computer, worried about the possibility that a disease outbreak was under way or that terrorists had released biological weapons.

After using a secure computer connection to check graphs and maps depicting where disease symptoms were being reported by county and by zip code, Gesteland knew within minutes that each incident was a false alarm:

· At 8:43 p.m. on Feb. 19, more than halfway through the Olympics, the alarm indicated that in Morgan County – one of seven Utah counties in the region where the games were held – the number of daily viral infections seen at acute-care clinics reached seven, just slightly above the alarm threshold of 6.69 expected cases per day.

· At 6:21 a.m. on March 3, four days before the Paralympics began, another alarm awakened Gesteland. It indicated that the number of patients seeking treatment for bleeding – whether bloody noses or rectal or vaginal bleeding – reached 33 in the seven counties within a 24-hour period. That triggered the alarm because it was somewhat above the expected level of 29.34 cases. At its worst, a sudden jump in bleeding cases might reflect a bioterrorism attack using the deadly Ebola virus.

While there was no real public health emergency during the Feb. 8-24 Olympics or the March 7-16 Paralympics in the Salt Lake City area, the sporting events provided a good test of the system Gesteland monitored – a system named Real-Time Outbreak and Disease Surveillance (RODS).

“If you’ve got a lot of people in the community getting sick at the same time with the same thing, this system will see it,” said Gesteland, an M.D. who is a National Library of Medicine fellow and graduate student in medical informatics at the University of Utah.

Reed Gardner, the university’s medical informatics chair, added: “This sort of system is essential as an early detector for bioterrorist events or for epidemics of any type.”

RODS automatically collected data in real time on about three-fourths of all patients visiting acute-care facilities in Salt Lake, Summit, Utah, Davis, Weber, Morgan and Wasatch counties. The facilities included nine emergency rooms and 19 acute-care clinics run by Intermountain Health Care, plus the emergency room at University Hospital and the polyclinic that served athletes and their families staying at Olympic Village on the university campus.

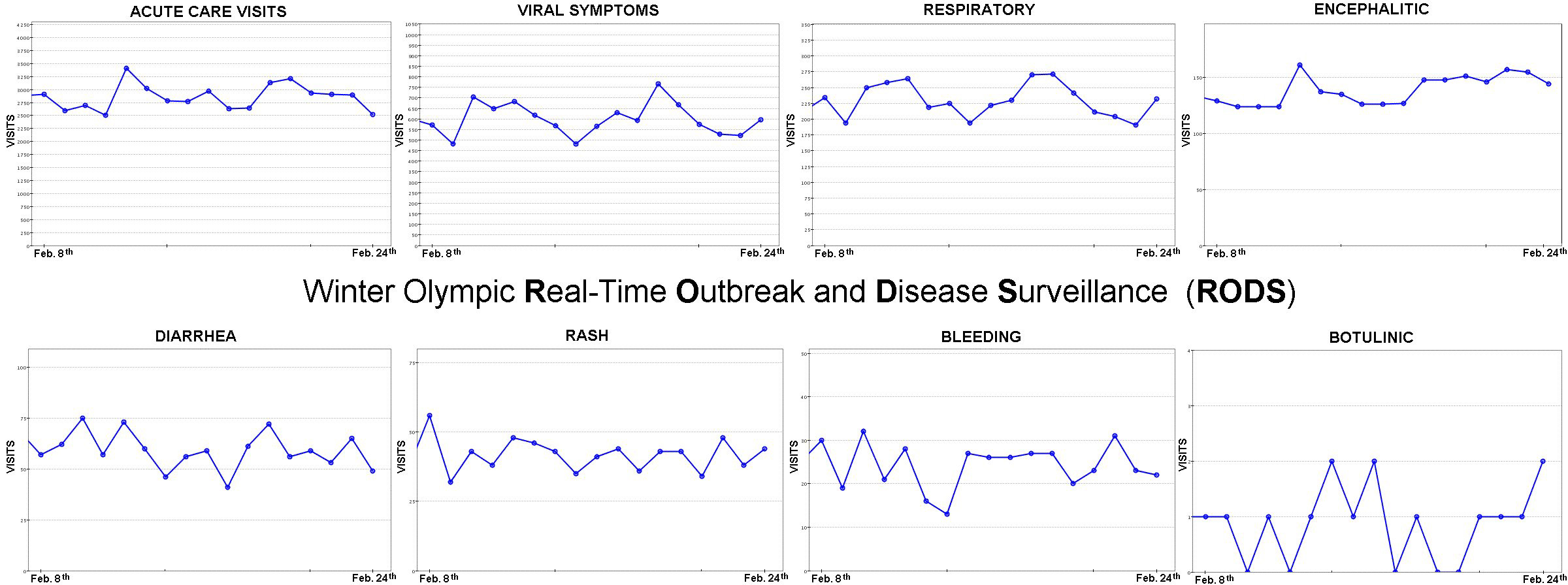

RODS tracked the total number of acute-care visits, plus seven types of symptoms: viral (such as sore throat, muscle aches, fever without other symptoms), respiratory (such as coughing, shortness of breath), encephalitic (headaches, dizziness, delirium), diarrhea, rash, bleeding and botulinic symptoms (drooping eyelids, difficulty speaking and other neurological symptoms that could indicate botulin toxin poisoning).

As always, staff members at the acute-care facilities recorded each patient’s name, account number, age, sex, birth date and primary complaint or symptom. But instead of staying solely within each facility’s computer system, the data also were sent automatically to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pennsylvania, where physician Michael Wagner and colleagues developed RODS. There, the data were processed, triggering an alarm if the number of cases of any symptom exceeded what would be expected normally.

When an alarm went off, automated text messages immediately were sent to Gesteland, to the RODS developers in Pittsburgh and to Utah’s state epidemiologist, physician Robert Rolfs, who was stationed during the Olympics at the epidemiological command center – known as the Epicenter – at Utah Department of Health headquarters.

Each time an alarm went off, Gesteland’s role was to examine computerized details, then consult by email and phone with the RODS Technical Advisory Group, which included Gesteland, Rolfs or another Utah Department of Health official, a Pittsburgh researcher and a local health department official from the county where the alarm was triggered.

If there had been a real disease outbreak or bioweapons attack, the Technical Advisory Group would have reported within two hours to a Policy Advisory Group – a team of officials who would have decided how best to respond.

Utah was in the middle of influenza season when the Olympics began, but RODS was adjusted to consider that factor, so flu cases did not trigger alarms.

RODS was only one of several monitoring methods used by federal, state and local health officials staffing the Epicenter during the Olympics. Officials also got daily reports of “notifiable diseases” which must be reported by law. They also kept track of patients at Olympic venue clinics and monitored “sentinel sites” such as hospitals, pharmacies, poison control centers and other locations where a disease outbreak might be first detected.

But RODS was the only method that could pick up a possible disease outbreak or bioterrorism attack within minutes to hours rather than the next day – or weeks later, as is the case with traditional disease surveillance, Gardner said.

Gardner said RODS would not have detected a bioterrorism attack like the mailing of anthrax-laden letters to a small number of people on the East Coast last year. “But if we had anthrax sent to 500 people in Salt Lake City, it would have detected that,” he said.

The idea of using RODS during the Olympics and Paralympics began when Gardner and Gesteland attended an American Medical Informatics Association meeting in Washington in November 2001. There, Pittsburgh’s Wagner made a presentation on how the University of Pittsburgh used RODS to track symptoms at 17 Pittsburgh-area hospitals.

Gardner contacted Rolfs, the Utah state epidemiologist – who also is on the University of Utah medical informatics faculty – and suggested using RODS during the Olympics. Wagner and Rolfs soon were in touch and efforts began to get RODS operating in Utah in a matter of weeks. Most of that time was negotiating the legalities. Gesteland said it took only a week to set up computer and communications equipment and software so the various acute-care facilities could share the data they normally collected anyway.

Gardner said it took much negotiating over privacy and other issues before the University of Utah, Intermountain Health Care (IHC) and state officials agreed to share patient information. “We dealt with this by having secure communications, legal agreements between institutions and having secure access to databases and only authorized access,” he said.

“We got two excellent health care institutions to cooperate” even though they normally compete, he said. “And we did it because of the Olympics and the 9-11 [terrorist attacks on New York and Washington] situation. Now that we have shown we can do it, the opportunity to continue it in the future is wide open.”

RODS still is running, and Gardner said the university is trying to get funding to keep it running permanently and to expand it so disease data also are collected from microbiology laboratories, pharmacies, private clinics and doctors’ offices and from a greater proportion of hospitals and acute-care clinics.

Ongoing use of RODS not only would monitor for bioterrorism, but watch for emerging infectious diseases, for routine outbreaks such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, and for upswings in breathing problems during bad air pollution episodes, Gesteland and Gardner said.

A few days before the Olympics began, President George W. Bush visited the University of Pittsburgh, where Wagner gave him a demonstration of the RODS system. In a speech soon afterward, Bush referred to the 1950s Distant Early Warning or DEW line that kept watch for enemy bombers that might cross the Arctic Circle to attack the United States. Bush referred to RODS as “the modern DEW line” to protect against bioterrorist attacks.

An electronic disease surveillance system is supposed to be implemented by the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gesteland said RODS’ Pittsburgh developers are hoping the CDC will choose their system.