March 8, 2004 — Using chicken embryos and colorful fluorescent dyes, University of Utah scientists have demonstrated for the first time in a higher animal that it is possible to simultaneously show three genes working within an embryo, body tissue or even a single cell.

“This method allows us to visualize how embryos develop in more detail and with greater clarity than ever before,” says physician Teri Jo Mauch, a pediatric kidney specialist at the University of Utah School of Medicine. “We can look at three different genes in the same embryo at the same time – even when they overlap. We haven’t been able to do that before in higher vertebrates such as birds and mammals.”

She says the technique also allows scientists to combine two-dimensional images of embryos in a computer to create a “three-dimensional image that we can rotate on a computer screen to examine the relationships between developing tissues and organs. There’s a lot we don’t know about how embryos develop. This technique will help us sort some of that out.”

Mauch says the new method should help research aimed at combating birth defects and creating artificial organs such as kidneys for people whose own organs have failed.

A University of Utah study describing development of the new method was published in the March 2004 issue of the journal Developmental Dynamics. Mauch – an associate professor of pediatrics and adjunct associate professor of neurobiology and anatomy – conducted the study with Pilar Garcia-Villalba, a postdoctoral researcher in developmental biology; Nathaniel Denkers, a laboratory specialist; Christopher Rodesch, a microscope and imaging expert at the medical school; and Kandice Nielson, a pre-med student.

The new method combines and expands upon three existing technologies for detecting genes: (1) in situ hybridization (ISH), a technique used to detect genetic material (DNA and RNA) in individual cells;

(2) immunohistochemistry, in which antibodies detect antigens that are linked to genes; and (3) tyramide signal amplification (TSA), which amplifies fluorescent dyes so they can been seen more easily when they are used to illuminate genes.

“We used existing technology and we applied it in a novel way” to illuminate simultaneously where three genes are “expressed” or active, Mauch says.

The new study is the first time any method has been used to simultaneously show the activity of three genes in a whole chicken embryo. Another method – colorimetric detection – has been used to detect three genes at once in fruit flies. A type of ISH known as FISH – fluorescent in situ hybridization – was used previously to show simultaneous action of two genes in frogs and in zebrafish by painting the genes with florescent dyes. Mauch’s method is an improved version of FISH. Her study’s title refers to it as “FISHing for chick genes.”

An Aid to Studies of Embryo Development and Birth Defects

The chicken “is a good model for human kidney development because, unlike frogs and fish, the chicken kidney develops in three stages like the human kidney,” says Mauch.

She says her method detects the expression of three genes even when they are active in the same tissue or within one cell. That helps researchers because “genes usually don’t act alone. Each step in embryo development involves more than one gene being turned on.”

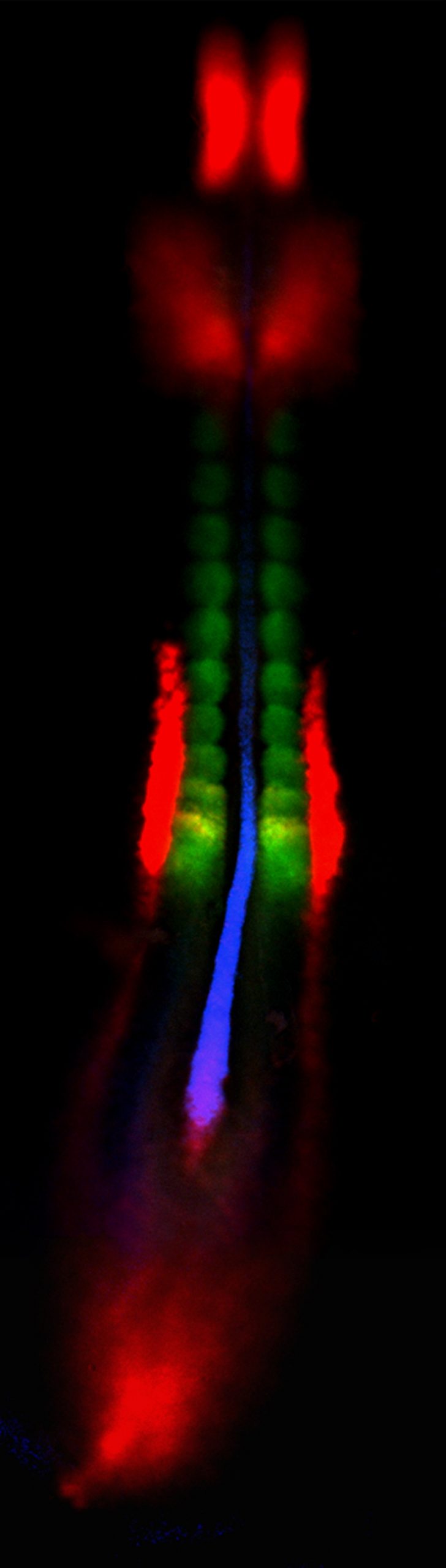

When two or three genes are active in one tissue or cell, the fluorescent colors overlap to form other colors. When genes labeled red and green overlap, the image is yellow. Red- and blue-tagged genes overlap to form purple. Overlapping blue- and green-tagged genes appear turquoise. When three genes overlap, red, green and blue combine to produce white.

Mauch’s improvement of the FISH method was combined with use of a “confocal” microscope – a microscope that focuses on a horizontal plane or “slice” within a three-dimensional object. The combination made it possible to see gene activity within a single cell.

It “allows you to see if the cell itself is expressing more than one gene, or if the color you see in the tissue is due to a mixture of cells, each expressing only one gene,” Mauch says.

The improved FISH method also is useful for showing where cells in an early embryo move, and what tissues, organs and body parts they become. Because genes active in a tissue dictate what organ that tissue will become, the method “can tell you what tissues will become what organs before they can be identified by their shape and size,” Mauch says.

Two-dimensional confocal microscope images also can be combined in a computer to make 3-D images of a whole embryo, allowing researchers “to look at the relationships of various genes, cells and tissues to one another during development,” she adds. That ultimately should help scientists “use tissue engineering to replace function that has been lost because of abnormal development or disease. By understanding in detail how the embryo develops, we hope to mimic the process with tissue engineering to make new kidneys, for example.”

How the New Method Works

Genes contain inherited instructions to produce proteins, which carry out almost every function in living organisms, including development of an embryo. When a gene is expressed or activated to make a protein, the first thing it does is make a copy of its genetic blueprint in the form of messenger RNA (mRNA), which is used as a template to make the actual protein.

Mauch says there are three basic methods for detecting mRNA to show where genes are active: FISH, which uses colorful fluorescent dyes to illuminate gene activity; the colorimetric method, which uses conventional dyes; and a method that attaches radioactive “tags” to tissues where sought-after genes are active.

The radioactive method is sensitive, which means it can detect low levels of a gene being studied, but the images lack detail. The colorimetric method is less sensitive, but shows better detail. Mauch says her improved FISH method “is very sensitive and gives you a good look at detail. And it gives you the benefit of looking at three genes at the same time.”

The three genes whose action was illuminated by Mauch’s method are active in the mesoderm, the middle of three layers in an embryo. The mesoderm becomes muscle, bone, cartilage, heart and circulatory system, and the urinary and genital system, including kidneys.

Mauch’s study used the new method to illuminate sites within a 36-hour-old chicken embryo where any of three genes were active: chordin, indicated by fluorescent blue; paraxis, labeled with a green glow; and pax-2, marked by fluorescent red.

The radioactive, colorimetric and conventional and improved FISH methods of detecting genes all use chemical “probes” to find and stick to mRNA from each gene being sought. Each probe is attached to an antigen (a substance that can be recognized by an antibody) that also gloms onto mRNA from the genes being sought.

Mauch preserved chicken embryos, and then exposed them in test tubes to the probes for the three genes with activity she wanted to illuminate. The probes and antigens hooked onto the mRNA from the three genes. Then the embryos were washed to remove probe material that didn’t hook onto mRNA. Next, one antibody at a time – each one attached to an enzyme named horseradish peroxidase – was added to each test tube with a chick embryo.

In the colorimetric method, the enzyme, which is derived from horseradish root, initiates a reaction that makes conventional non-fluorescent colored dyes precipitate within the cell where the targeted genes are working. But only two colors at a time can be seen using this method, and thus only the activity of two genes. Furthermore, it is not possible to see two or more active genes overlapping in the same tissue or cell.

Mauch’s improved FISH method overcame those drawbacks by combining conventional ISH with the new, commercially available TSA gene-detection kit that contains fluorescent dyes and a chemical that amplifies their color. The horseradish enzyme is used in FISH to activate the fluorescent dyes so they attach to sites where the genes are active. The TSA kit makes even more dye attach to areas of gene activity.

The study – part of a larger project to understand kidney development – was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and by the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation.

“If we understand normal development, then we might learn how to prevent birth defects,” says Mauch.