Sept. 6, 2012 – University of Utah engineers mapped white blood cells called eonsinophils and showed an existing diagnostic method may overlook an elusive digestive disorder that causes swelling in the esophagus and painful swallowing.

By pinpointing the location and density of eosinophils, which regulate allergy mechanisms in the immune system, these researchers suggest the disease eosinophilic esophagitis, or EoE, may be under- or misdiagnosed in patients using the current method, which is to take tissue samples (biopsies) with an endoscope.

These findings are published as the cover article in the September 2012 issue of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Despite the limitations of current detection methods for EoE, the study authors say biopsies remain the current standard of care, but the engineers are working toward new diagnostic methods that could be available in five years.

In EoE, eosinophils typically found in the bloodstream invade the esophagus and start chewing away at its lining. Often triggered by food allergies, EoE symptoms overlap with other disorders such as acid reflux.

“The gold standard for understanding this disease is detecting the location and presence of eosinophils in the esophagus. Unfortunately, eosinophils are not uniformly distributed within the esophagus, which can lead to underdiagnosis,” says study co-author Leonard Pease, assistant professor of chemical engineering at the University of Utah. He is also an adjunct professor of gastroenterology and pharmaceutics.

The University of Utah team showed that even a patient with known EoE would require more than 31 random tissue samples, or biopsies, from an area in the esophagus with low eosinophil density to reliably diagnose EoE. Currently, if a patient is suspected of having EoE, five to 12 biopsies are collected along the esophagus using an endoscope. If more than 15 eosinophils turn up in any one of these samples, a diagnosis of EoE is made.

“This is the first quantitative assessment of how eosinophils are distributed in the esophagus,” says co-author Gerald Gleich, professor of dermatology at the University of Utah and specialist in eosinophil-related diseases. “Until now, someone would go in and snip around, but they wouldn’t have this map to quantify the degree of infiltration of this disease in relationship to the actual anatomy. These findings impact how many biopsies a doctor should perform.”

Since eonsinophils are scattered within the esophagus, EoE can go undetected until severe symptoms surface, ranging from painful swallowing to chest pains that mimic a heart attack.

“This is not the ideal way to diagnose EoE,” says Pease. “If the distribution of eosinophils was 100 percent uniform, it wouldn’t matter where you sample, but in fact it’s patchy. Our mapping shows if you sample in one region, no diagnosis would be made, but if you took another region about an inch away, the same patient would appear to be severely diseased.”

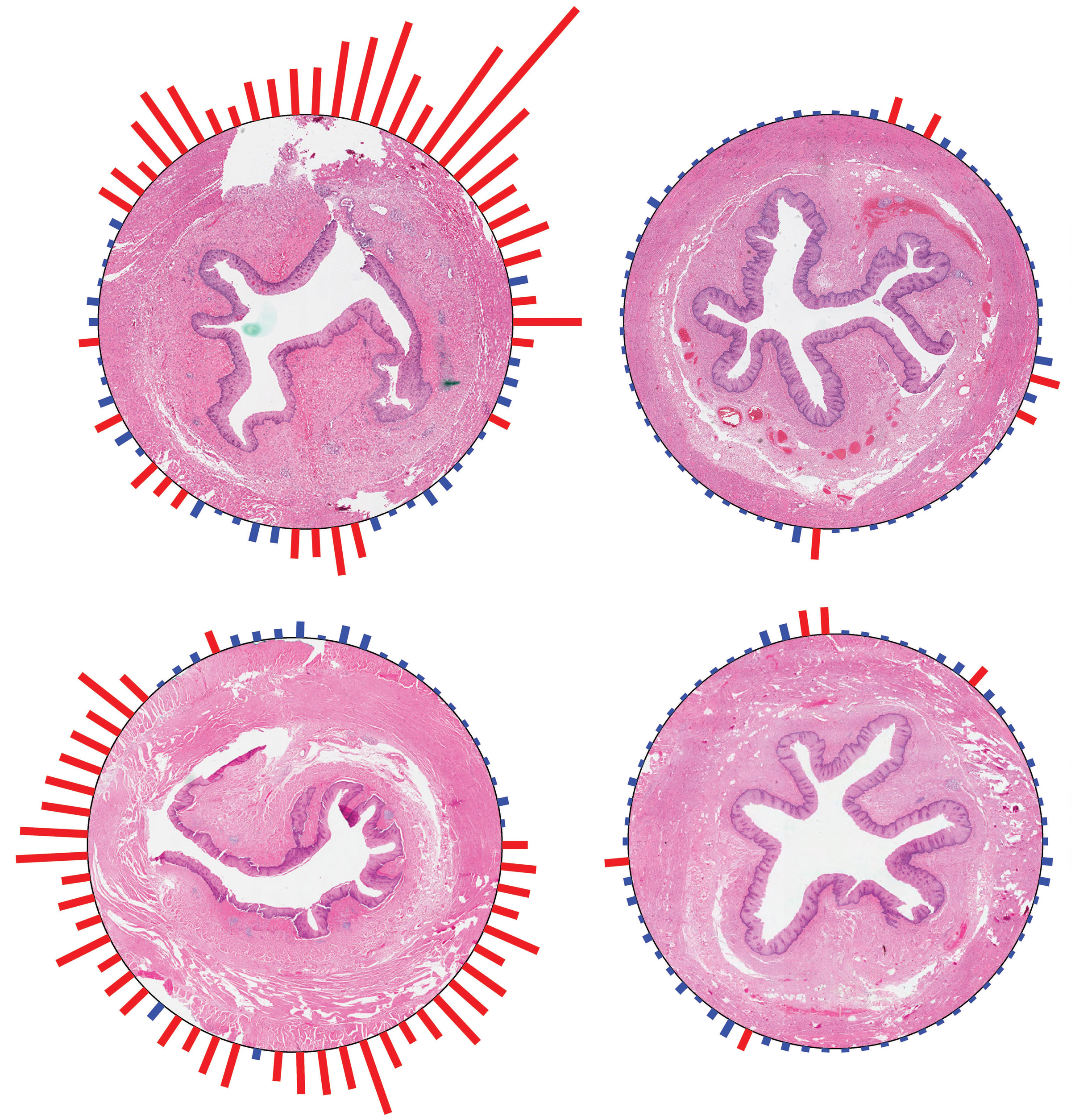

To generate a map of eosinophil distribution in the esophagus, lead author Hedieh Saffari examined each of 17 tissue sections taken at intervals every one-eighth to one-fifth of an inch along the esophagus of a known adult EoE patient. A typical adult esophagus is 10 inches long. “For every cross section, I used microscopy to count the number of eosinophil cells along the entire perimeter of the tissue surface in each high-power field of view image,” said Saffari, a chemical engineering graduate student. “There were somewhere between 40 and 120 of these images per cross section so it took a lot of time, but it was worth it to extract the information we were looking for. No one has done this type of mapping before.”

Saffari’s diligence paid off. With her painstakingly collected data, she and Pease used a statistical simulation technique to determine whether randomly sampling tissue would result in a positive diagnosis of EoE based on eonsinophil density.

“Our analysis shows that with current diagnostic conventions, you are only going to catch the patients with medium-to-high eonsinophil densities, which means we may be misdiagnosing patients as much as one out of every five times,” says Pease. “Given this data, clearly endoscopy is not sufficient for a disease this patchy.”

Gleich says their findings will inform future revisions of EoE diagnosis guidelines, but biopsies are “currently the standard of care and will not change in the near future.”

Building on this study, Pease and Saffari are investigating technologies for labeling and detecting proteins shed by eosinophils in the esophagus, which would help detect EoE at an earlier stage. They have also filed a patent to use radiolabeled antibodies to map eosinophils throughout the entire esophagus, a new technique that would be evaluated with a clinical trial. “We’re optimistic that such a diagnostic tool could be available in the next five years,” Pease says.

Saffari adds this is part of the team’s long-term goal to develop new strategies to enhance EoE diagnosis and understand what causes the disease.

Pease, Gleich and Saffari conducted the study with gastroenterologists Kathryn Peterson and John Fang and pathologist Carolin Teman at the University of Utah. This study was funded by the University of Utah, the Utah Governor’s Office of Economic Development and the National Science Foundation.